Within product teams, between product teams, and with stakeholders, there can be conflict. In the 1960’s, an American psychiatrist named Stephen Karpman mapped out three roles that people play in conflict. He created a model that illustrates destructive interaction, and called it the Drama Triangle. (Karpman loved the dramatic arts, and found these archetypes to be roles we play, or masks we put on, in conflict scenarios.)

The Hero

The Hero (also called the Rescuer) wants to save the day. But the action is often a quick fix that makes the problem go away, not a long-term solution. The Hero is motivated by wanting to be right. And this can result in acceptance and praise from others, but their heroics are limited in effectiveness and don’t address the underlying issues. Often a Hero might jump into the middle before knowing all of the facts, so a true solution wouldn’t be possible.

The Villain

The Villain (also called the Persecutor) wants to place blame. They want to figure out who is at fault and throw them under the bus. Occasionally they blame themselves, but more often they point the finger at someone else. Many times the blame goes to an undefined “they”, in the form of blaming “management” or “engineering”. When you are speaking with a Villian, it can often feel like gossip.

The Victim

The Victim is driven by fear. They pursue personal safety and security above all else. Victims can list many reasons why they are the real victim of a person, circumstance, or condition. “I was never trained on that”, “There’s not enough time”, “Nobody is helping”, “I’m not allowed to talk to customers”, etc. The Victim operates from a place of powerlessness and helplessness. Victims will seek help, creating a Hero to save the day, who often perpetuates the Victim's negative feelings and leaves the situation broadly unchanged.

Note: In this model, Victims are acting the part, they are not actually powerless/being abused. But accusing someone else of “playing the victim” and gaslighting them is a classic Villain move!

In 2009, a way to distrupt these interactions was published. David Emerald created The Empowerment Dynamic (TED*) which stops the reactive nature of the Drama Triangle and empowers new roles.

VICTIM > CREATOR

Victims stop thinking “poor me” and become Creators. Victims are reactive - focusing on scarcity, considering themselves powerless, and not seeing choices. Creators, however, claim their own power in a situation and focus on possibilities. Creators take responsibility and look for what they can do to alter a situation.

VILLIAN > CHALLENGER

The Villain stops blaming and becomes the Challenger. Where the Villain points finger about the present situation, Challengers bring new perspectives to others through positive pressure in a way that creates a breakthrough. The Challenger inspires and motivates, a kind of teacher who points the Creators opportunities for growth.

HERO > CoACH

The Hero stops trying to save the day and becomes the Coach. The Coach is a support role, helping others create the lives they want and evoking transformation. Heroes take over and micromanage. Coaches facilitate and encourage. A Coach leaves the power with the Creator, not taking it for themselves.

Shifting to the empowered roles instead of the sabotaging ones has to be a conscious move, but one that can be implemented within a team that has good trust and psychological safety. Conflict and tension will always be present to some degree, but we can better manage it and our reactions to it.

STAND-UP EXERCISE

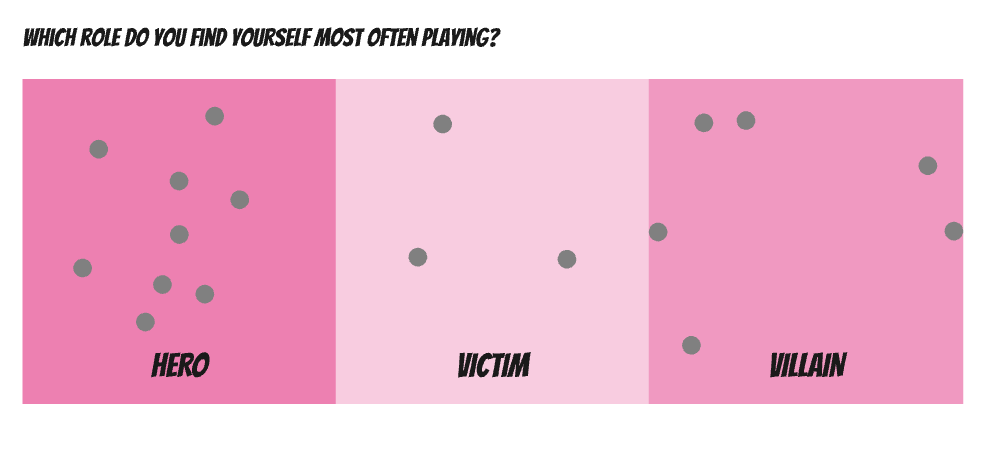

Present The Drama Triangle and Empowerment Dynamic to your team. Use this 3 minute video to help illustrate. Talk to your team about what roles they most often play, and in which scenarios. One person might always choose the same role, or they may play different roles based on the people or circumstances involved. How can your team support each other when they see the drama roles surfacing?