Most product teams care deeply about quality. But when timelines tighten or pressure increases, quality often becomes a vague, emotionally loaded concept. One person worries we’re moving too fast. Another one worries we’re overthinking. Conversations stall because we’re using the same word to mean different things.

Quality isn’t a single standard you either meet or miss. It’s a set of attributes that compete for attention. And different moments in a product’s life put different kinds of quality at risk.

Quality Isn’t One Thing

One of the most useful ways to talk about quality comes from Ami Vora, who describes four distinct dimensions teams are constantly balancing:

Performance — how fast, responsive, and reliable the product feels

Bugs — correctness, stability, and freedom from defects

Completeness — whether the solution actually solves the full problem

Consistency — coherence across flows, surfaces, and behaviors

Every team makes tradeoffs across these dimensions. That’s not a failure; it’s reality. The problem arises when those tradeoffs are implicit. When no one names what’s most fragile, teams start talking past each other, and quality debates become personal instead of practical.

When quality discussions stay abstract, they tend to escalate quickly. Engineers may feel asked to cut corners. Designers may feel pressure to ship something unfinished. PMs may feel caught between speed and responsibility.

But when a team can say, “This quarter, completeness is the riskiest thing for us,” or “Performance is the edge we can’t afford to dull,” something shifts. The conversation becomes about judgment, not virtue. It frees you up to focus on intent, not blame. Naming risk creates shared context. It gives teams language to explain decisions and empathy for why others feel tension.

Where Quality Risk Shows Up

You can usually spot quality risk by paying attention to where friction accumulates.

Where are we cutting scope, and what kind of quality does that affect? Are we creating an experience that feels partial or awkward to a user?

Where are we deferring work, and what assumptions are we making about impact? Are our inconsistencies eroding trust with other teams?

Where are customer complaints, internal friction, or workarounds starting to cluster? Are there bugs that felt acceptable individually but now feel risky in aggregate?

Each of these points to a different dimension of quality, and recognizing which one matters most at this moment is what enables better decisions. The goal isn’t to eliminate risk. It’s to make it visible. When teams agree on which kind of quality is most fragile, they can protect it more deliberately, communicate tradeoffs more clearly, and move faster with less friction.

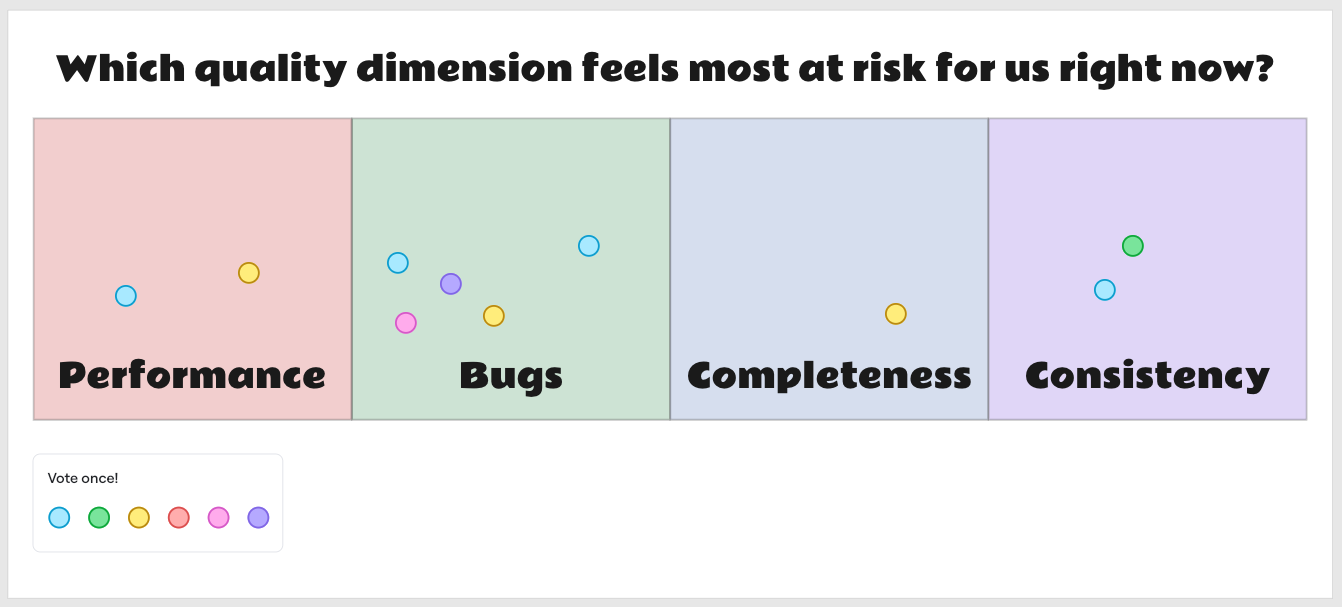

STAND-UP EXERCISE

In your next stand-up, on a shared workspace ask the team to vote on one question:

Which quality dimension feels most at risk right now?

Performance · Bugs · Completeness · Consistency

Notice where there’s alignment, or surprise. Invite people to talk about why they voted the way they did. Listen for patterns across roles or perspectives. Engineers, designers, and PMs often see different risks, and all of them are valid signals.

Going forward for this sprint / quarter / release explicitly name which quality dimension you’re prioritizing, and which one you’re consciously putting at risk.