Books are written, podcasts are produced, TedTalks are given, all about product and product teams. So much so that it can seem like there is only one correct way to build a product team. However, a more encompassing approach might be to take an Agile mindset to building a product team. At its root, a product team is a cross functional team (a team with members from different functional areas) who are united to design, develop, and ship a product that fulfills the target user's needs.

How that team is comprised can vary. The core components of responsibility can be met by specialists or generalists. You can have just a couple folks on the team or enough to eat two pizzas. Your organization may have both a product and a project structure, which introduces a new set of players.

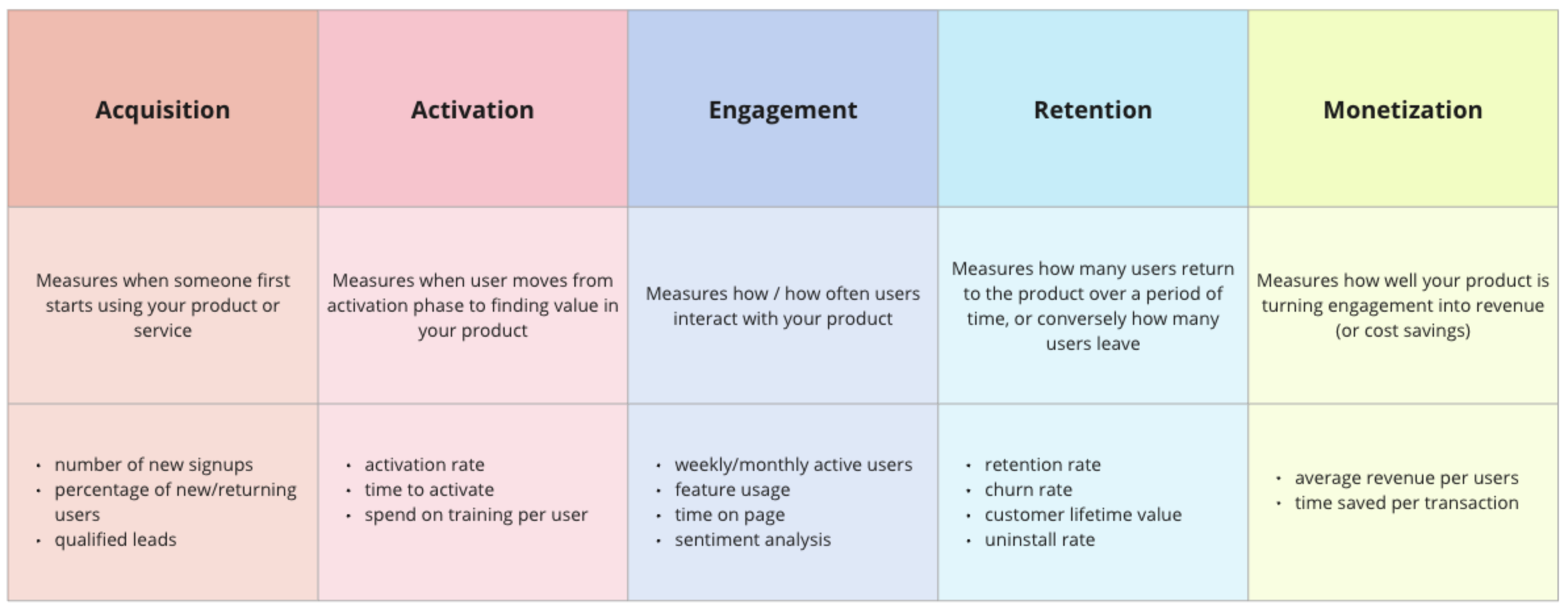

Regardless of who is on the team, responsibilities should be defined. Everyone on the product team should know their role. This chart is generally what we shoot for within the teams I manage - from a product perspective. This chart does not include engineering roles. In a different organization, you might also want to add a product marketing role, or more.

Note that the headers of these columns denote a role on the team, not necessarily a job title. The team just needs to agree on who is performing what role.

The idea is that with agreement on who does what within the team, there is more empowerment for that person to take responsibility for the items within their jurisdiction. There is more individual autonomy and accountability, which leads to better team autonomy and accountability. The visibility into each other’s roles also allows for more communication within the team.

Teams evolve over time. New roles are needed as the team matures; folks leave and don’t get replaced; the product changes and requires a different setup. Periodically, the team should evaluate what is working and what might be missing. Iterating on the team construction is also part of the Agile process.

If you are a director or portfolio manager, you may also need to consider how you structure your product teams within the larger organization. There are just as many options here, which we can perhaps cover in the future.

STAND-UP EXERCISE

A product team should all agree on roles and responsibilities. If you do not have a responsibilities chart like the one above for your team, you should construct it. An Agile coach or a manager can help bring an unbiased eye if there are any questions or discrepancies in jurisdiction.

One you know who is doing what, a good discussion can be “who are we missing”? If another person could be added to the team, which role would be most beneficial to add them into? Portfolio managers, this is a great exercise to see if your organization is under-emphasizing certain areas of product management.